Reflections on Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival (final weekend)

I was lucky enough to make it to the final Saturday afternoon and the Sunday of Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival. The programme of events was richly varied and, to my surprise, often playfully humorous. What follows isn’t so much a review, as some personal thoughts and reflections on what I heard.

Saturday 26th November

Pat Thomas solo improvisation

Pat Thomas’s technique is one that reworks the dimensional space of the piano’s keyboard and the body that engages with it. Flowing across the keyboard, fingers dance quickly and independently before, suddenly, the side or palm or back of the hand turns to impress the keys. One sees a painter move from fine brushes to those for broader strokes, and back again. Thomas impacts the keys and follows excesses, yet also locates moments of subtlety that sit starkly alongside these extremes.

The (notational) basis of the performance were standards (he was playing from the Real Book, I think). The spectre of familiar tunes gave shape to raw physical forces. Or rather, the tunes where shown only to be located through these forces – this was part of the strenuous effort of his pianism. The standards were guiding concepts that disappeared as quickly as they appeared; they emerged under and out of these moving hands, rather than as discrete messages dictated by the fingers. The performance was a document of someone who lives performance of these melodies and harmonies, such that the performance cannot simply reproduce these tunes, but – in performance – draw attention to the manner of performance itself. Thomas treated the audience to multiple playful encores.

Australian Art Orchestra with Cath Roberts and Mandhira de Saram

This was a rare and valuable project that brought together Aboriginal and Europeanist musical practices. This felt substantial, a collaborative process based on a relationships between people who wanted to share and build something together, rather than a passing or notional encounter. A number of pieces embraced a sense of place, in the use of field recordings or through direct sonic and narrative reference to local birds. At other times, drones or repeated patterns would propel us forward; occasionally we’d settle firmly into a groove. This was a musical project that afforded something shared in the collective act of music-making. At the same time, it was a pleasure that one could also appreciate each player’s musical personalities in their distinctive contribution.

Sunday 27th November

Andrew Zolinsky plays works for piano / piano and electronics

Lilja María Ásmundsdóttir’s Tracing opened the concert. We heard some wonderful textures and transformations, with Andrew Zolinsky at the piano and Ásmundsdóttir triggering prerecorded material and attending to live sound processing through Ableton Live. The prerecorded material, I found out afterward, was recorded during a previous installation work that decomposed a piano into its constituent elements. In Tracing, the piano is put “back together”; from the textures of the extended techniques attendant to the piano’s different elements, often inside the piano, eventually emerged a somewhat neo-romantic tune played at the keyboard, returning us to the familiar through the unfamiliar.

Two short pieces followed. Barry O’Halpin’s three-minute Miniature punctuated the programme, unfurling complex harmonies reminiscent of Debussy or Scriabin – though as if sketched by M.C. Escher. This harmonic language was contemporary, yes, yet – as with Ásmundsdóttir’s piece – reminded us of something to which we are more accustomed. Next, Zolinsky’s performance of Her Wits (About Him) by Donnacha Dennehy wonderfully explored the paradox of the singing line within the ebbs and flows of ongoing movement. Melodious and rich, though in a way different from O’Halpin’s approach, both these pieces were familiar yet new, offering the audience faded colours of old photographs that one happens across years later.

I thought that Chris McCormack’s Something Other Than the Fear of Falling was very successful. This demanded great physicality and dexterity from Zolinsky, who was asked to jump across and around the keyboard, revisiting repeated if altering forms returning as objects heard. For me, at least, there was a sense of observing objects within a shared gravitational field, mutually jostling and clashing within it.

Linda Buckley’s Water Witch, like the opening work from the programme, was for piano and electronics. This explored flows of material, with for example the depths of the piano’s low end approached as a morphing mass that blurred the communication of the distinguishable pitches. At other times, a fragile clarity would counterpoint with this, becoming present like the outlines of a rocky shoreline only apparent in the troughs of the waves above. I was particularly struck by an extended passage in which the electronics provided a foggy mirroring of the piano.

Eugene Ughetti plays works for solo percussion

The performance room/”womb”

Thomas Meadowcroft’s March Static opened this programme of UK premieres of Australian works for percussion. This first performance choreographed – in a board sense – Eugene Ughetti’s movement around the space, and pauses with his snare drum to deliver isolated gestures, predominately repeated strikes or rolls that crept into and out of audibility. Drifting from speakers around the audience were fragmented sonic materials that, like the snare drum gestures, connoted the military march – sometimes dreamlike material composed of acoustic melodic materials, electronic sound, and additional percussion. The concert took place in the Town Hall, but not simply in its hall; the audience were seated within a kind of womblike “tent” that asserted an intimate performance space, adding to the experience of immersive sound. At the same time, the often hard edges of the percussive sounds and objects that made them contrasted with the soft walls and lighting which, while womblike, for me also recalled a medical or forensic tent, a place for examining traces of causation.

This was followed by Alexander Garsden’s Tremolo for gong, transducer, and mobile microphone. The microphone picked up the vibrations of the transducer via the gong, and fed this back to the transducer (as well as the speaker that the audience hears); tones emerged from this feedback, and these shifted and changed depending on the position of the microphone held parallel to the gong. What results was a focused investigation of the gong as resonant object, an object that offers a range of sonic possibilities. I enjoyed this greatly (but then I am a sucker for feedback…).

Nina Buchanan’s Outward Pressure followed this. A kind of deconstruction of some of the principles of dance music, with Ughetti playing a partial drum kit tightly alongside a pre-recorded track of drums and synth, with both often fracturing the expected rhythmic patterns of electronic dance music. Most effective for me was the use of the hi-hat, from which Ughetti teased out a range of timbres, playing across it in various ways – this was given extended focus in at least one part of Buchanan’s composition. This aspect provided a different framing of timbre, and its percussive delivery, a structuring principle that is so central a resource in electronic music production.

Martin Del Amo’s Inaudible consisted of a choreographed, serialised set of movements, approaching the percussionist as a kind of mannequin. The movement material was distinctly unnatural. What I liked here was that this playfully recast “the percussionist” (as a figure, rather than Ughetti specifically). This figure is such a skilled technician of a range of instruments and objects – or even a drum “machine”, as we’d just heard in Buchanan’s piece. Here, this principle was taken to a ridiculous limit, with the body of the percussionist – that machinic vehicle for precise rhythmic gestures as instructed by the composer – here directed but rendered mute.

Liza Lim’s piece for woodblock, An Elemental Thing, finished the programme. This was a highlight, in that in found such nuance in an object that is apparently so simple. The woodblock was activated with various techniques, including rubber beaters dragged across its surface, finger strikes, and – later – a bullet vibrator. The mechanical and organic where complicated where, for example, the performer is asked to use their forearm to cover the open face of the woodblock, creating vowel-like formants. And so Ughetti here took on another role, as conjuror that asks the inanimate to “speak.”

Explore Ensemble play Mark Fell’s Every non-empty ultra-connected compact space has a largest proper open subset (2022)

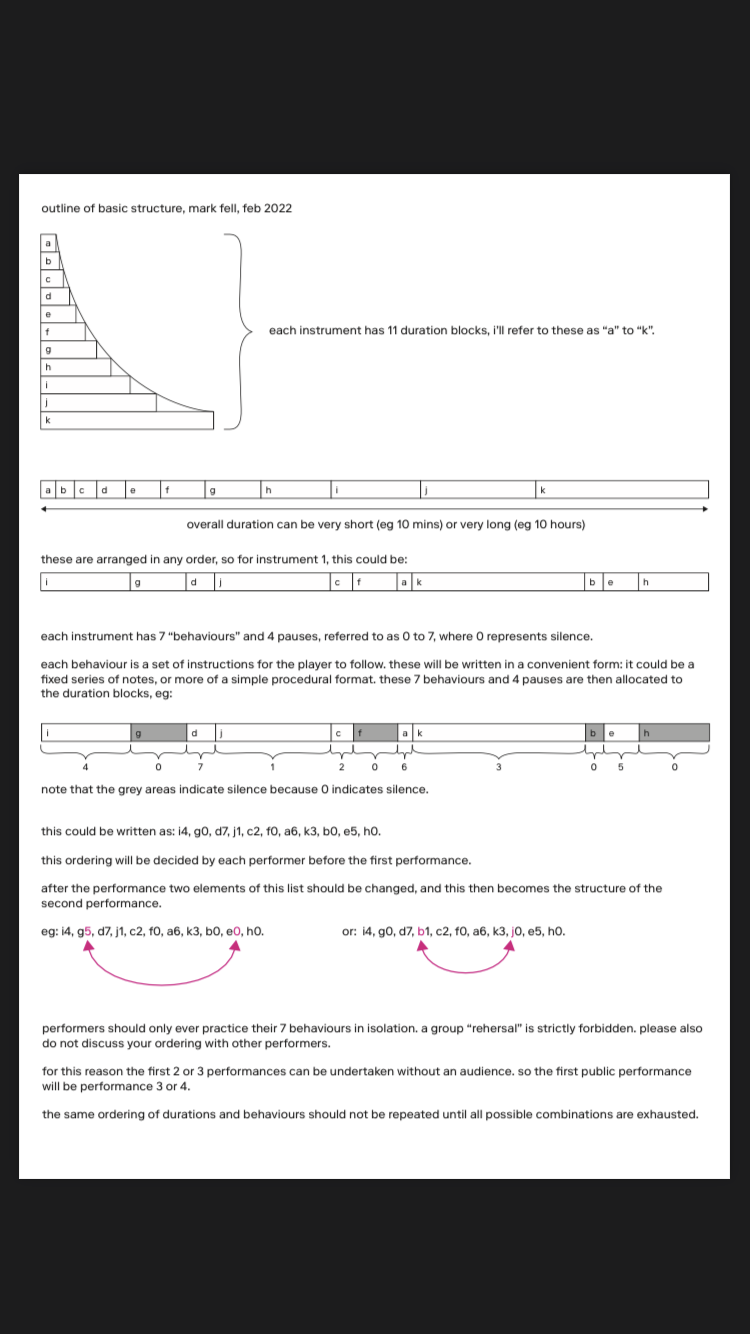

Screenshot of outline of ‘Every non-empty…’, accessible by QR code during the performance.

The final concert of the festival. The piece was constructed through the combination of a set of different durations, each combined separately by each player. During each durational section, different kinds of behaviour would take place. (Some players’ sections would also be silent, so not all would be always playing simultaneously.) The six soloists are instructed not to rehearse together or discuss their construction of the durational sections or behaviours, meaning that the layering of different players’ materials is only heard for the first time in the public performance. Two documents, which could be accessed by the audience using a QR code in the venue, explained this process. The players performed in a line, with half the audience each side; a final sonic layer consisted of a field recording played from speakers that surrounded both audience and players.

The resulting situation led to intense focus. Some of the clusters or sustained tones conjured a Feldman-like stasis; others where more active or energetic, casting the player momentarily as a “soloist,” standing apart from the other players who would temporarily comprise an ad hoc “ensemble.” Such casting of roles was, of course, unplanned at the level of composition, yet at the same time an effect that was probable, given the kinds of materials that players were given to work with. There was a composition of probabilities. For me personally, it took maybe 15 or 20 minutes to attune to what I was hearing; around this time something clicked, and I entered a different state of listening. This is the kind of music that needs to be perhaps 5 minutes or almost an hour or more, but would fall flat if anything in between.

One telling moment came when, in the field recording, we hear a member of the public approach Fell, and ask him what he is doing, to which Fell replies he is making a recording for a piece to be performed in November. This is a music of observation and of attention, but one that also testifies to the active place of the composer in the making of attention. One is not simply a “modest witness” to what is heard.

I’d find myself drawn to listening to one soloist at a time, or to combinations of instruments that would, without apparent reason, uncombine. I was hearing probability rather than causation. Halfway through I was struck by an image: an array of six coloured lights – the six soloists – each turning off and on in different combinations, such that any one moment glowed with a distinct admixture. I’d also hear resonances between the ambisonic soundscape and this, that, or these instruments. And so the lights cast their hues onto this sonic environment.